First up in our Spotlight on Emerging Scholars Series: Dr. Shanmugapriya T discusses her work employing the cutting-edge features of digital humanities and literature to study water scarcity issues in her home of Coimbatore — and explains how digital mapping can be harnessed as a tool to narrate historical impacts on the environment.

Can you speak about your research area? What drew you to this work?

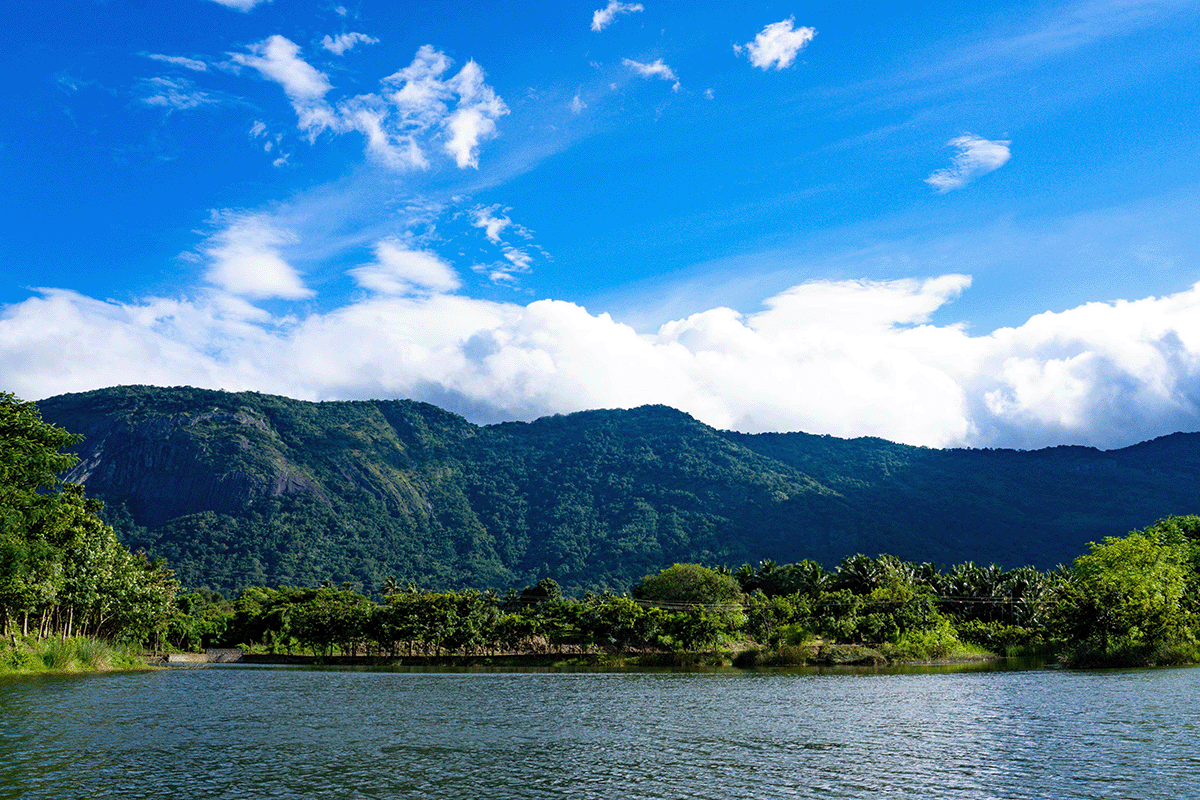

My research employs the cutting-edge features of digital humanities and digital literature to study the humanities broadly — and particularly environmental issues. Three things drew me to this research: my expertise in digital technologies; my interest in digital poetry, arts and history; and my lived experience as a farmer for eleven years in Erode, Tamilnadu, India. After defending my PhD at the Indian Institute of Technology Indore (India), I began to combine these three rather diverse skills and my experience to study the water scarcity issues in Coimbatore, the southern region in India where I was raised and educated.

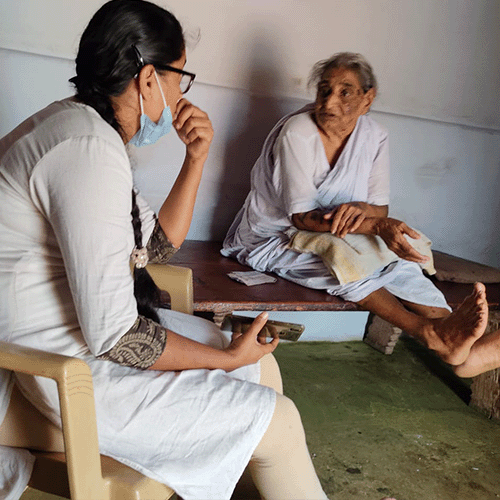

My research uses diverse data sets, such as historical and literary corpora, historical maps and oral testimonies, to trace the transformation of Coimbatore’s water tanks from the British colonial era to the present. I have completed two digital narrative projects: Digital mapping of British India Coimbatore water transformation (1916-2021) and Digital poetry of Lost Water! Remainscape?

Currently, I am mining information concerning water from digitized historical corpora by experimenting with various algorithms.

What can digital mapping tell us about history and the environment?

Digital mapping can tell us a lot about history and the environment. It can be harnessed as a tool to narrate the historical changes and impacts in the environment due to climate changes, man-made disasters, and other potential causes. The dissemination part comes in handy in digital mapping, so that we can share it with researchers and the general public for public engagement.

For example, the digital mapping I created reflects changes in the water tanks in terms of their size and encroachments due to both climate changes and mismanagement. I used georeferenced historical maps that are digitized and archived at the National Library of Scotland. These historical maps are imbued with many nuance details about the environment, including mountains, rivers, channels, and water tanks, and the interlink between water bodies.

Three things drew me to this research: my expertise in digital technologies; my interest in digital poetry, arts and history; and my lived experience as a farmer for eleven years in Erode, Tamilnadu, India.

The digital mapping is developed based on these details and it particularly tells us about the disappeared (red colour) and shrinking (blue colour) water tanks in the Coimbatore region from British India Coimbatore to present (1916-2021). It also includes details such as the type of tank: whether it is small, medium, or big; the type of encroachment like building and/or agriculture lands; the source of water: where the water comes from, for example, through interconnected water tanks channel or rivers or even from a big tank; and the source name: the water bodies names. After independence, Coimbatore was divided into four districts: Coimbatore, Erode, Tripur and Karur. This digital mapping reflects this current divisions. One can use this digital mapping to trace water tanks changes that occurred in within two hundred years.

Tell us about your digital poetry project. How did it come about?

I perceive electronic literature as a potential method for digital humanities, in general and particularly digital environmental humanities project. For example, in our couple of articles, I and my co-author Deborah Sutton theorize how we can deploy electronic literature as an innovative method and a dissemination tool: The Digital Poetics of Lost Waterscapes in Coimbatore, South India and Electronic literature as a method and as a disseminative tool for environmental calamity through a case study of digital poetry ‘Lost water! Remains Scape?’ to address societal and environmental degradation.

Digital creative narrative can visualize our vision, objectives and outcomes of our project aesthetically and meaningfully. Based on the research outcomes from the digital mapping, qualitative study of historical and literary texts and field visits, I created a piece of digital poetry Lost Water! Remainscape? with help of technicians Jagadeesh, Dharan Raj and Mohanapriya. It represents the waterscape of past and present through its multifarious narrative components: text, hypertext, digital literary entities, videos and images.

However, there are some challenges, too. The digital platform WordPress, where my project is embedded, now hampers the dissemination part. The poetry is created through software and languages like Blender and Adobe Animate, HTML and JavaScript. The customized WordPress web page would not permit us to edit to add these entities. Like most institutions, Lancaster University, in which I worked previously with Deborah Sutton who was PI of the project, helped us to host our project through WordPress due to various administrative reasons. Although this platform would not allow us to edit the default settings, we managed to edit it and embedded the poetry. However, the interface of the digital poetry is now disrupted owing to frequent site updates from WordPress.

Now I am looking for options like minimal digital approaches and funding to host the poetry as a separate web page. Currently Bhavani Raman and I are encountering similar issues for her project. We are working to move to minimal approaches against ephemerality of web products.

Digital mapping … can be harnessed as a tool to narrate the historical changes and impacts in the environment due to climate changes, man-made disasters and other potential causes.

Tell us about your collaboration with Professor Bhavani Raman. What’s coming up next for the project?

I am working with Bhavani Raman on her project ‘Decolonizing Archives of Water: Data Justice and Critical Cartography for a Postcolonial Coastal City, Chennai’. We are currently in the process of developing web platform for the outcomes from the project. Two important outputs are underway. One is building a web page to display a countermap. It visualizes a monsoon storm in the coastal city of Chennai, India from the perspective of fisher community knowledge. Besides this, we are digitizing various water related entities in the historical maps of Chennai. I assist Raman’s work study students in terms digitizing data points and story maps.

We are excited to share these outcomes online soon!

What are three things you want people to know about your research?

- I’m building and applying digital technologies for Humanities research in general, specifically, digital mapping, text-mining and digital creative visualizations.

- I’m applying digital humanities methods to study environmental challenges in general, specifically water-related issues.

- I’m developing and applying theoretical and applied digital humanities for domain-specific research areas. For instance, I am currently working on building and mining a British colonial India corpus, an Indian English novel corpus, and am building models for mining dragomans’ Italian translations of Ottoman records.

What writing projects are you working on now?

- I’m building a domain-specific historical corpus based on concept-models — a case study of the British India colonial corpus (1833 to 1966).

- I’m writing on the failures and re-learning of first-generation digital humanities researchers from Global south.

- I’m examining the critiques of digital mapping of water tank transformation from British India Coimbatore to present.

- I’m writing Learning by redoing: Building Computation Modelling for the Corpus of Indian English Novels (1947–2017)

What’s on your writing playlist?

Usually, I don’t play any music when I am writing. But sometimes I do enjoy music when I work in public places like a café.

Shanmugapriya T is a Digital Humanities Postdoctoral Scholar at the Department of Historical and Cultural Studies (HCS) at University of Toronto Scarborough. Her research and teaching interests include an interdisciplinary focus in the areas of digital humanities, digital environmental humanities, and digital literature and games. She is particularly interested in building and applying digital tools and technologies for Humanities research.

Shanmu holds her PhD in Digital Humanities and Indian English Literature at Indian Institute of Technology Indore, India. She was an AHRC Postdoctoral Research Associate at Lancaster University, UK from 2020 to 2021. Previously Shanmu was a SPRAC Fellow at Lancaster University in 2019. She is the Electronic Literature Organisation Fellow 2022. She has published papers in national and international avenues such as Oxford University Press, Digital Humanities Quarterly, Routledge and Electronic Book Review etc.

Shanmu is a digital artist and works with other digital artists as well. She created a digital poetry with gaming mechanics ‘The Lost Water! Remainscape?‘ She collaborated with digital artist Andy Campbell for their digital poetry and digital game projects The Lost Oasis and The Water Cave and upcoming their digital game on Karur Water Tanks.

Shanmu created an interactive map of the transformation of waterbodies from British India Coimbatore to present (1916-2021). She developed a prototype web application called ‘Neer’ using Python to extract specific information related to the history of water from historical texts. She has coded appropriate filters and specifically calibrated this application to deal with variations in spellings in toponyms of colonial India.

She teaches courses ‘Games and Play’ and ‘Reading and Unreading Digital-born Creative Works: Critical Making of Contemporary Information’. Shanmu offers DH workshops and research consultation for faculty and researchers at HCS.