By Ariana Ellis

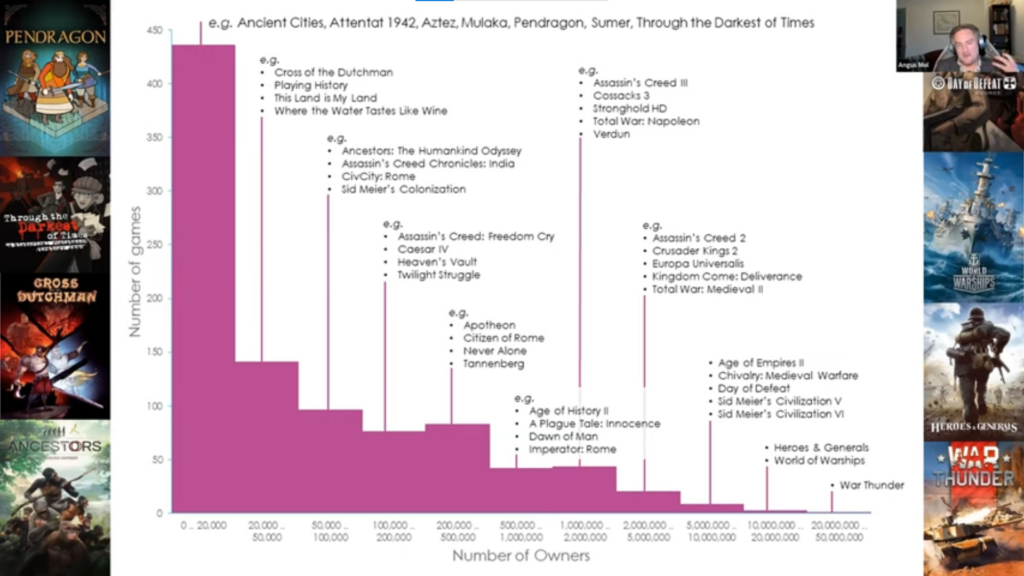

Between 2010 and 2016, humanity collectively spent 1,200,000,000 hours in the world’s six largest museums. This may not surprise you; however, what might is that this is the same number of hours people have spent playing Sid Meyer’s video game, Civilization V. This is just one among many video games in the Civilization franchise within the larger collection of historical games available to the public.

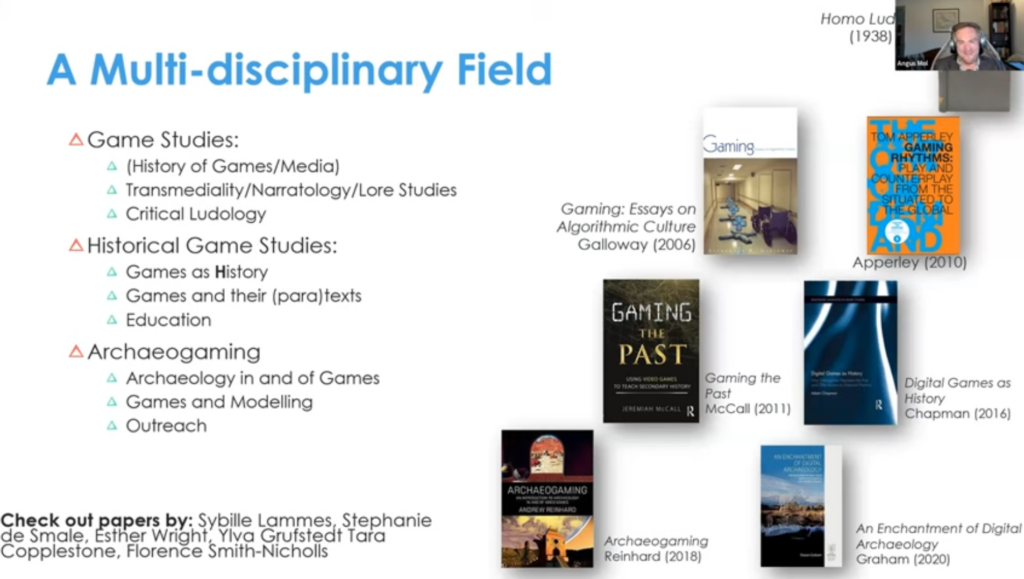

Dr. Mol referenced this information during his presentation as a visiting scholar for the University of Toronto’s Critical Digital Humanities Initiative on March 11th 2022. His lecture, “Playful Time Machines: Research and Outreach at the Intersections of Video Games and the Past” was wide ranging, and explored the foundational concepts of game studies, historical game studies, and archeogaming; the communal networks of game distribution platforms like Steam; and the connections between play, game design, and social impact. From the range of topics addressed, this post will focus on the connections between play, game design and social impact, which aligns with Dr. Mol’s particular interest in how the past is re-created and experienced through play in contemporary video games, and my experience teaching about video games and history.

The idea of bringing video games into academic study and the classroom is polarizing. Not everyone recognizes the importance of studying games, and as Dr. Mol describes some find them difficult to analyze because games, being immersive experiences, have very little text and cannot be easily broken down into individual components. In the classroom, it is not only professors but also students and sometimes their parents who find the idea of studying video games in a humanities context confusing. In 2021 I developed and taught a course at the University of Toronto that examined the relationship between History and video games entitled, ‘Gaming the System: Perceiving the Middle Ages in Video Games’. At the start of the course, I received several emails from students who were worried that they had signed up for something other than a history course. During class discussion in the following weeks a few students shared that choosing a course that involved video games had disappointed their parents, some of whom refused to pay for the games required on the syllabus. This was not unexpected or surprising to me. I have often had to explain why I feel it is important to teach about video games and history, reasons which align very closely with Dr. Mol’s discussion of the impact of video games.

These reactions are also encountered beyond the classroom. Game designers have expressed exasperation with academics’ fixation on historical accuracy. Dr. Mol describes Sid Meyer, creator of the Civilization franchise, as essentially saying that those who critique these games have ‘too much time on their hands’ and ‘need to play more’. This reaction feeds into the popular stereotype that video games are childish and superficial, for example, the still popular trope of the ‘manchild’ playing games. Fuelling this stereotype allows game creators to dodge and downplay very real issues of racism, orientalism, and sexism that pervade historical games and gaming culture. Dr. Mol discussed the number of large game studios that do not want to engage with the social context of their games (though Ubisoft appears to be making some changes). These studios justify their position by saying, “[p]laying out someone else’s political philosophy is not fun for the players.” and “[…] we don’t want to take a stance in current politics. It’s also bad for business […]”. This perspective on game creation ties in with the concept of ‘The Magic Circle’ that Dr. Mol discussed in depth.

Essentially, the Magic Circle is the field on which play occurs. Earlier versions of this circle had it closed off from reality, creating a bubble where you could lose yourself entirely in another world. In reality this circle is quite ‘leaky’, as Dr. Mol described. You never really leave your world behind; certain elements of your life are inevitably drawn into play, others are actively removed, and then on the margins are ‘playful’ experiences, like re-enactments. Outside the circle are experiences meant to be serious, such as museum visits or classrooms, however these ‘serious’ spaces are quickly intersecting more and more directly with the Magic Circle as interactive heritage exhibits and playful pedagogy continue growing in popularity. It is becoming obvious that separating play and ‘serious’ study is difficult because the line between play and learning is impossible to clearly define. What is fun or playful to one may not be to another, and it has been shown[1] that episodic memories (memories associated with narrative) are ingrained deepest during learning. Play provides a huge range of opportunities for this kind of learning to occur. Dr. Mol’s examples showed us how in many ways this is already happening; the Aztec site Huey Teocalli which was included in Civilization VI had a significant increase in google search hits after the game’s launch, and the search popularity of the site has remained higher ever since.

The idea that video games can exert a strong influence is a perspective that many share. According to Dr. Mol, 90% of players who choose historical games believe that video games can change someone’s perspective on a historical event. Dr. Mol reflected that with so many hours spent in these worlds, it “[…] will shape in some sense at least the type of worlds […] that you see as being possible”. With this in mind, it is important to remember that games are ‘designer pasts’. Dr. Mol described this process – how game studios take what occurred in the past and branch it out to create a somewhat plausible future that will maximize players’ fun and enjoyment. This includes generating ‘authenticity’, the aesthetics and game elements that players will recognize as historical and allow them to increase their world immersion, regardless of how historically accurate these details are. In combination with the choice that some games studios make to ignore how social issues connect to their creations, this can lead to players integrating ‘authentic’ but deeply untrue elements of history into their imagination of the past. Two areas where this commonly occurs are depictions of race and gender. Video games will often replicate an all-white and male dominated past (particularly in medieval games) because that is what many players will accept as ‘authentic’. The dangers of this are clearly demonstrated by many alt-right groups who have followed old patterns and weaponized these concepts of the Middle Ages, and also show up in many more subtle forms. Dr. Mol demonstrated how this view of the past showed up in Reddit board debates surrounding the game Battlefield V, which allows players to play as a female character, and also integrates characters of colour into the game. The Reddit board became so inundated with debates surrounding the inclusion of non-white and non-male identities in a WWII game that the moderator eventually closed the boards and banned further discussion on historical accuracy. However, as Dr. Mol said, “[it was] actually about the place that women have in todays’ video games […]” as well as the impact of the white mythic space, which Stefan Quiroga discusses in his book exploring “Race, The First World War, and Battlefield I”

So how to counteract these issues? The biggest stumbling block that Dr. Mol identified is one that the heritage industry is also attempting to address: “People care deeply about the pasts they play in [and engage with] but the vast majority of play takes place without any direct communication with the channels that produce knowledge about the past.” For example, when a museum creates an interactive exhibit, how can they ensure that visitors take away the information they intended? Similarly, video games create engaging, immersive, and effective experiences where players take in information about the past, but even games created by socially aware studios (usually independent studios, according to Dr. Mol) have no way to guarantee that the player will absorb accurate information. This is where groups such as Dr. Mol’s VALUE Foundation become essential. VALUE aims to break out of the ivory tower and put knowledge at play by highlighting playfulness, accessibility, and contextual knowledge to integrate games into curated learning experiences, which allows anyone who wants to learn more about the history behind the games they play to find resources. Teachers and professors can also integrate games into their classroom environments. I find that when I include games and play in my teaching (both for my video-game centred course and more traditional history courses) students are instantly more engaged and more likely to raise questions and offer opinions. They become more comfortable in the classroom environment because they realized that the atmosphere can be playful and allow room for mistakes without repercussions. Including video games in the classroom allows the instructor to become the mediator who can teach about the past while simultaneously providing students with examples of how to critically analyze the games they play.

The influence of video games is an ever-growing phenomenon. An article in The Atlantic from March of 2022 describes how the game Europa Universalis was a driving force for many students to enroll in history courses at Cornell University, and how a player whose job required a deep knowledge of Turkish history and culture had to “unlearn” ideas he’d absorbed while playing the game. This is not to say that games are inherently bad or dangerous, but their impact cannot be sidelined. There are programs dedicated to analyzing literature, film, and other media. Video games are now proving to be even more influential on current and future learners. Dr. Mol described how digital humanities tools can be used to critically analyze games and their impacts, and his talk demonstrated how important these investigations are. The sooner higher education can move past the idea that play is childish or non-academic, the faster we can utilize the incredible potential play and games have to offer and engage more directly with our students. As Dr. Mol said: “[p]eople want to play in and learn about authentic pasts, so let’s engage with them in those places where play is made and takes place. [Let’s] play more – in academia, outside of academia, beyond the ivory tower, inside the ivory tower.”

Ariana Ellis is a doctoral candidate at the University of Toronto, studying late medieval and early modern history. Ariana’s work focuses on the interaction between popular culture and the civic rituals of public execution in London and Venice between 1400 and 1600. She employs methodologies of social, sensory, and emotional history, as well as digital humanities.